Back in 1954, Austrian architect Richard Neutra published his classic Survival Through Design, a visionary book that foresaw the neurological implications of design. Neutra charged and challenged architects to be conscious of the powerful influence they wielded in affecting the psycho-physiology of occupants through the buildings they designed and constructed.

At a time when High Modernism extolled the virtues of a minimalistic aesthetic with abstract geometries and stark volumes, Neutra warned against the pursuit of conceptual paradigms divorced from the imperatives of our biology and its essential lifeline to the patterns found in natural environments.

In one of the book’s most memorable passages, Neutra asks: what is the utility of a tree?

At the time, the architect decried the emerging trend: splitting matters of design into questions of utility versus aesthetics. In his view, the latter were fast becoming ancillary to the only concern of large commercial projects: return on investment (ROI). Neutra voiced his famous question as a matter of beauty’s incommensurable value in architectural design where it shouldn’t be parceled off as trifling with ornamentation.

Now, 70 years after this architectural scholar and the father of Biorealism, a term he created to encompass the importance of nature’s beauty and distinct geometries in design, his question continues to reverberate. In fact, his insights, which preceded the biophilic design movement by decades, has found sure footing in a field he first heralded intrinsic to design: cognitive neuroscience.

Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder

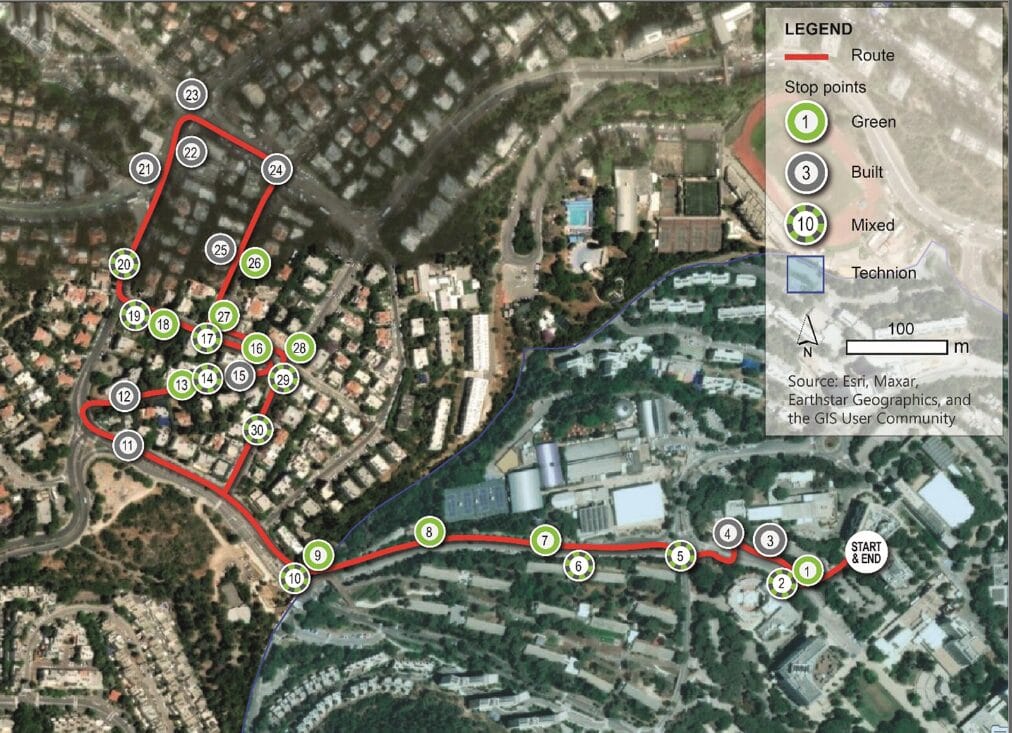

A new study, The Nature Gaze, conducted by Bangor University and the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology may very well have answered Neutra’s famous question by revealing that urban dwellers who steered their attention towards trees and foliage during a 45-minute city walk rather than looking at man-made structures reaped significant health benefits, including reduced anxiety and a more pervasive feeling of mental and physical restoration.

The trio of academic researchers led by Dr. Whitney Fleming, Brian Rizowy, and Assaf Shwartz, who devised the study instructed 117 urban residents to take a simulated walk to and from work in a metropolitan area while wearing eye-tracking glasses. One group was instructed to favor looking at green natural elements like tree lines and foliage during their walk; a second group was told to spend their time looking at grey man-made elements like houses and buildings while a third group was instructed to split their time by directing their visual attention between green and gray elements. 1

The research team analyzed the eye movements and patterns from the three groups after having taken pre and post-measures of cognition, affect, anxiety, and perceived wellness. The data revealed that the group who spent more time in visual contact with foliage, trees, and natural elements like well-tended gardens and other green spaces reported a decrease in anxiety and higher levels of restoration.

The findings, published in the peer-reviewed journal People and Nature, reaffirm earlier empirical studies that have consistently found that exposure to natural environments yields psychological benefits resulting in greater emotional restoration, with lower instances of tension, anxiety, anger, fatigue, confusion, and total mood disturbance than urban environments with limited characteristics of nature. 2

We Are the Trees

The physiological effects of exposure to nature are also well documented. One notable study from The Economics of Biophilia, an award-winning white paper by Terrapin Bright Green, documents the biometrics of taking a walk in the forest versus an urban footprint. By comparing the salivary cortisol, blood pressure, and heart rate of subjects in both groups, the team revealed that the forest walkers had, on average, 13-15% lower salivary cortisol, which is a stress hormone, than the urban walkers.

The most impressive metrics were the changes in the parasympathetic and sympathetic activity of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which regulates our relaxation and flight-or-flight responses. The subjects exposed to the forest walk had a powerful autonomic relaxation response measured by a 56% increase in parasympathetic activity (relaxation) while sympathetic activity, which rises during stressful situations, decreased by 19%.3

In the more than half a century since Richard Neutra asked what was the utility of a tree, its abundant benefits to human health, wellness, and to our global ecology have been proven beyond a shadow of a doubt. Yet, the fact that “we are the trees,” in the words of American poet Mary Colborne-Veel, who says “we are the trees, our dark and leafy glade, bands the bright earth with softer mysteries” must quicken humankind’s resolve as the fate of trees is but ours, too. 4 Hence, beyond the cognitive cues that eye-tracking technology underscores, Neutra’s argument that it is foolhardy to split matters of utility from deep beauty has never seemed clearer.

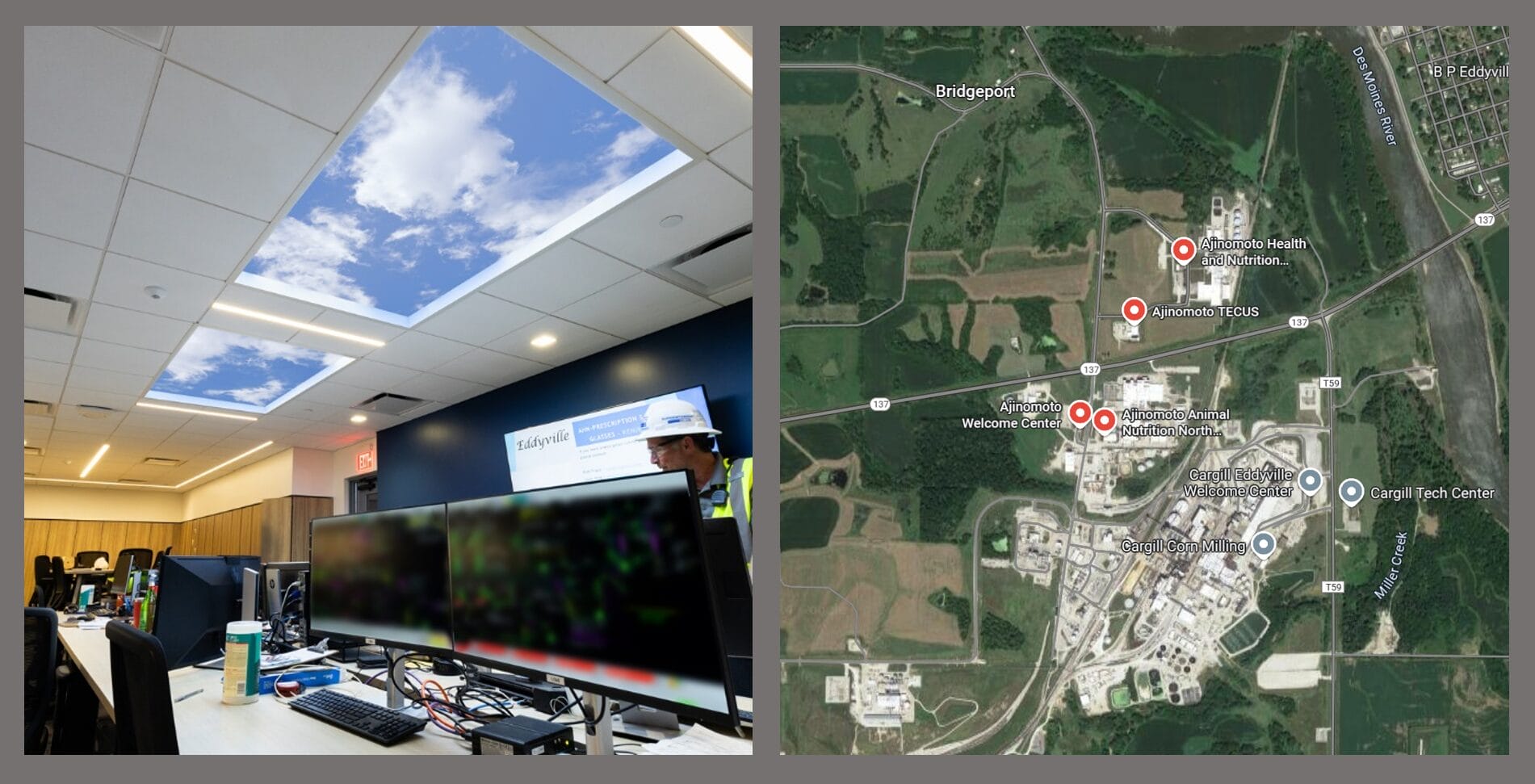

OpenView Luminous Virtual Windows

In large metropolitan areas, oftentimes deep plate buildings like major hospitals and commercial buildings there are few if any lines of sight to green spaces like parks, waterfronts, or tree lined boulevards. Furthermore, staff also spends the lion’s share of their shifts and working time in the enclosed areas of a building. In situations where it is not possible to provide the restorative benefits of biophilic lines of sight, large scale biophilic illusions of nature offer an evidence-based alternative.

OpenView Luminous Virtual Windows offer large scale panoramic scenes of natural environments that mimic the human eye’s extraordinary depth of field. By employing a deep stack photographic process it is possible to generate a composite image of remarkable detail. The ultrarealistic view results from a sequence of photographs taken from the same POV, first focused on the foreground and then shifting along the field of depth until the deep background is the point of focus. When the entire series is merged into a single image using processing software, the result is stunning detail that attains a most vivid fine-art quality when backlit using calibrated daylight-quality lighting.

References

1 Fleming, Whitney, Brian Rizowy, and Assaf Shwartz. “The Nature Gaze: Eye-Tracking Experiment Reveals Well-being Benefits Derived from Directing Visual Attention Towards Elements of Nature.” People and Nature, vol. 6, no. 4, 2024, pp. 1469–1485. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10648.

2 Terrapin Bright Green. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health & Well-Being in the Built Environment. P. 13, 2014. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/14-patterns/

3 Terrapin Bright Green. The Economics of Biophilia: Why Designing with Nature in Mind Makes Financial Sense. 2012. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/economics-of-biophilia/

4 Mary Colborne-Veel, Song of the Trees. Accessed November 4, 2024. https://poets.org/poem/song-trees