This article was first published in the October 2018 issue of Radiology Today magazine as a web exclusive.

There’s a growing interest among health care architects, radiologists, and neurobiologists to solve the most intractable design problem in imaging environments: claustrophobia associated with enclosed interiors and the technology that, even in an open MRI, remains foreboding. In 2017, there were more than 74 million CT and 36 million MRI procedures performed in the United States. Given the pervasiveness of imaging procedures as diagnostic and therapeutic tools, what has kept environmental designers from counteracting the anxiety brought about by our innate aversion to confining and intimidating technology?

Google “How to Deal With Claustrophobia in an MRI” and the top three organic search results yield a list of tips from, eg, Fox Health News, the University of Virginia Health System, and the Center for Diagnostic Imaging. Patients are exhorted to breathe, make small talk, visit before the visit, pray, or, in the words of one therapist, “desensitize yourself to whatever it is that triggers the feeling of being terrified.” Sedation and hypnosis are highly recommended.

What’s lacking is a deeper understanding of the emotional and cognitive needs of the patient, who, surrounded by formidable devices, is isolated and vulnerable. Where does he or she turn for empathy?

Environmental Cues

So far, we’ve attempted to provide empathy through reminders of nature. Many radiology environments replace acoustic tiles with backlit photographs of nature scenes. Often, they are installed with utter disregard for spatial orientation, scale, perspective, or even gravity. A department manager might opt for a mountain landscape on the ceiling—after all, patients will lie on their back, and their feet will point in the direction of the “earth” while the “sky” will be near their head.

In order to reduce the feeling of claustrophobia, the standard understanding suggests we can remind the patient of a pleasant place. However, in terms of how the eyes and brain process visual content, placing a landscape on the ceiling may create confusion and is, at best, the equivalent of attempting to soothe thirst with a picture of a glass of water.

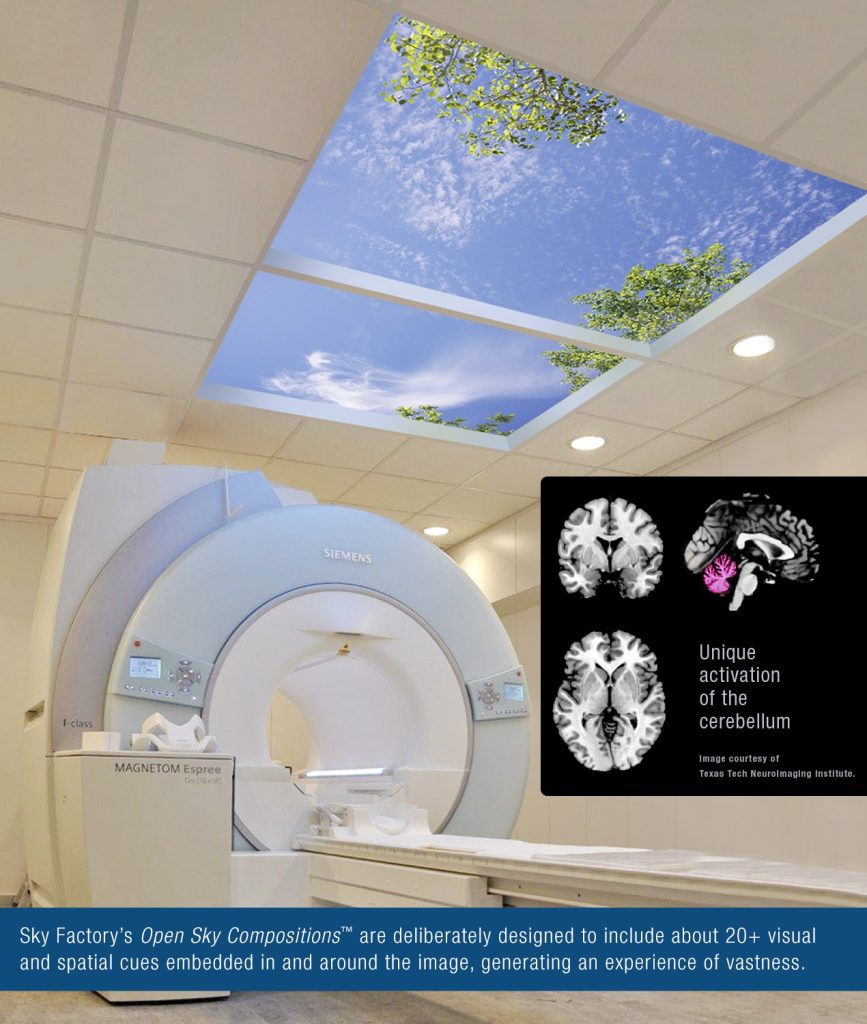

In the last few years, the neurobiology of visual processing has revealed that it is possible to trigger a genuine psycho-physiological response of vastness, even in the confines of radiology vaults. By capturing, composing, and staging a photographic Open Sky Composition within a realistic architectural opening, the result is a genuine virtual skylight embedded with more than 20 contextual cues. The additional data imbue the image with multisensory cues that engage an area of the brain involved not only in visual processing but in spatial cognition and depth perception as well.

Such a multisensory image of the sky is not perceived as a flat, one-dimensional surface, but as a palpable volume. The cognitive sleight of hand comes courtesy of the power of visual illusions that “trick” our habits of perception into making assumptions based on previously experienced spatial patterns. In his paper Biophilia & Healing Environments, Nikos Salingaros, a mathematician and polymath known for his work on architectural theory, notes that “our brain automatically computes the gravitational balance of forms” and as a fundamental environmental cue, it reduces stress.

Furthermore, Jennifer Groh, PhD, a neuroscientist at Duke University, emphasizes that our memory is a repository of spatial maps. We identify and recall our surroundings based on discrete spatial reference frames, the stored spatial maps of previously experienced environments. In other words, the neurobiology of sensory processing reveals that when we mimic appropriate environmental cues that our neural pathways associate with open space, we can, in fact, generate a visceral illusion of perceived open space. This can readily be accomplished in patients about to undergo or engaged in an MRI or CT procedure.

Recent Research

At this year’s biannual conference of the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture, Sky Factory presented an abstract, “Applied Cognitive Architecture and The Restorative Impact of Perceived Open Space,” based on a 2014 neuroimaging study published in the peer-reviewed Health Environments Research & Design Journal. Since the study’s publication, the findings have earned awards from the Design & Health International Academy, the Environmental Design Research Association, and Planetree International, a patient advocacy nonprofit organization.

The study was the result of multidisciplinary collaboration between an architect, a neuroscientist, an environmental designer, and a visual artist. The study, Neural Correlates of Nature Stimuli; an fMRI Study, was led by one of the most published researchers in healthcare design, Dr. Debajyoti Pati, of Texas Tech University.

The study examined whether there were unique patterns of brain activation associated with subjects exposed to deliberately composed photographic sky images, as compared with other positive and negative images as well as neutral photographic images. The positive impact of nature images on health outcomes has been traditionally measured using behavioral and physiological indicators. In the past, there has been a lack of understanding of the underlying neural mechanism that explains the observed positive influence.

However, this study generated brain maps of the neural pathways and regions associated with subjects’ perception of a series of Open Sky Compositions created by a team of artists led by Bill Witherspoon, chief designer at Sky Factory. The study found that the Open Sky Compositions shared all the brain activation present in the positive images of nature. Of particular interest to the researchers were the activations found in the cerebellum, which is often associated with spatial cognition. The unique neural activations revealed by the brain maps suggest that the deliberate way in which Sky Factory artists layer, compose, and stage these Open Sky Compositions is a key component in triggering spatial cognition.

These brain scans confirmed that it’s possible to alter a patient’s experience of isolated confined interiors by deploying a more powerful therapeutic intervention. Furthermore, a cognitive approach that dissipates claustrophobia not only increases throughput by virtue of its effect on patient distress but also boosts staff wellness by imbuing imaging vaults with an experience of unexpected vastness.